Rua M. Williams · @FractalEcho

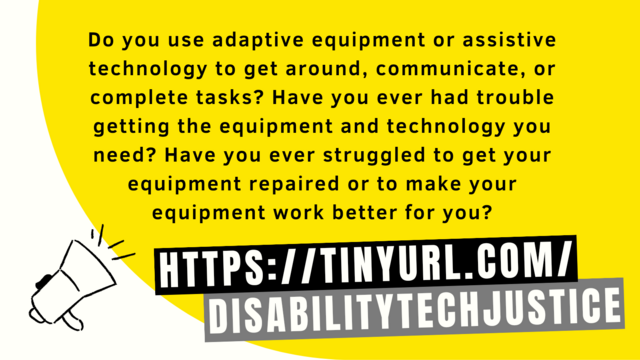

712 followers · 1146 posts · Server kolektiva.socialResearchers at Purdue University are studying how disability and technology policy can change to make life better for people who use adaptive equipment and assistive technology.

If you use any of the following:

• Mobility equipment like wheelchairs, scooters, canes, walkers, prosthetic limbs, and more

• Dexterity equipment like hooks, grabbers, or other specialized manual tools

• Communication equipment like a talker or other AAC Device

• Assistive Software like Screen Readers, voice over, or eye trackers

• Adaptive computer interfaces like specialized keyboards, mice, buttons, or switches

• Or other similar devices

You are invited to participate in our study “Adaptive and Assistive Technology Users, Developers, and Technology Policy”, Purdue IRB 2022-759.

Survey link: https://purdue.ca1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_eYjuUSH5moUOuQS

This survey of your experiences will take 10 to 20 minutes of your time and will help us transform technology policy to improve quality of life for Americans with disabilities.

#ColiberationLab #TechJustice #DisabilityJustice #Disability #AdaptiveEquipment #AssistiveTechnology #TechnologyPolicy

#ColiberationLab #TechJustice #DisabilityJustice #disability #adaptiveequipment #assistivetechnology #technologypolicy

Rua M. Williams · @FractalEcho

671 followers · 1093 posts · Server kolektiva.socialPlain language summary of "Metaeugenics and Metaresistance: From Manufacturing the ‘Includeable Body’ to Walking Away from the Broom Closet

I will start this summary by explaining the title. I usually skip that part. This time I am going to explain the title because the title is so long, and so annoying. In "Academia" (which is just a fancy way to say college), there is a joke about how professors choose titles for their papers. It's not a specific joke. But everyone likes to make fun of titles that go like this "short catchy title": "long title with complicated meaning". I choose this kind of title a lot, because I think it's fun. I don't take myself too seriously.

The first part of this title is "Metaeugenics and Metaresistance". Something-ics is a kind of science, or a way of thinking, like economics, or politics. Eugenics is a way of thinking that says there are good bodies and bad bodies, and that human beings have a moral duty to keep their bodies "good" and to only have children with "good" bodies. Eugenics also says that governments are responsible for making sure their citizens are only people with "good" bodies. Eugenic science was overtly racist and ableist.

Most people believe that eugenics is over. They believe it was a bad science that happened in the past, and that we don't believe in it anymore. The problem with believing eugenics is over is that it makes it hard for you to notice when it is still happening. When more black and Indigenous people die from a virus, some people understand that this is because of racism in medicine. But when more disabled people die, we think it is because their bodies are weaker - That they do not have "good" bodies. The truth is that disabled people are dying more not /just/ because they are vulnerable but also because we made public choices that endanger their lives.

We made these choices because we still believe in good bodies and bad bodies. We still believe that it is everyone's moral duty to make their body as strong as possible. We still believe that some people deserve to die because of the body they are in. This is metaeugenics.

For something to be meta- is for it to exist without being said or written out loud. It is important to be clear that when we say disabled people, we do not mean just white disabled people. Understanding metaeugenics helps us to understand why we are okay with so many disabled people dying. It also helps us to understand that black and Indigenous people are not just vulnerable to racism, but to ableism also, even when they are not disabled in ways that are obvious to us. Because we do not care about disabled people, we allowed black and Indigenous people to be put at greater risk from racism in public health. Metaeugenics can help us understand how racism and ableism work together.

Resistance means to work against something. In this paper I want us to think about the ways we can work against metaeugenics by paying attention to metaresistance. To notice metaresistance, you have to think differently about what you are seeing when you see people resisting something. You have to notice both what someone is directly working against, and also notice how that resistence “speaks” or does resistance against other things that are not clear - like metaeugenics. I will give some examples later.

The next part of the title is “manufacturing the includable body”.

The “includable body” is something disability scholars write about. When we talk about inclusion, we usually mean that society should be open and accessible to everyone, no matter their disability. But when we “do” inclusion, schools and workplaces usually set some rules about what a person must do or be or look like in order to be included. Some scholars that write about this are Tania Titchkosky, Sara María Acevedo, Joe Stramondo, Eunjung Kim, and Anne McGuire. When a disabled child has to “earn” their place in the mainstream classroom by graduating from certain therapies, this means they have been made “includable”.

This is one way we uphold metaeugenics. We make disabled people work to make their bodies “includable” in therapies before we will accommodate them in “mainstream” spaces. Disabled people are morally obligated to make their bodies as “good” as possible, and if they don’t, they are called “non compliant”.

If you know anything about inclusion, you might be a little confused. Inclusion is a right! In the United States, we have the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act which means disabled people have the right to accommodations to access public life, work, and school. Unfortunately, rights and laws do not work without people doing the right thing. Even if you have the "right" to be included, who decides what counts as inclusion?

The problem with rights is that someone else is always in charge of deciding what "counts".

The United Nations has the Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (CRPD) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). In my paper, I try to explain that when you put these documents together, they show a global metaeugenic attitude toward disability. The CRPD says that disability must be recognized as a natural part of human diversity, but that adult decision makers have the authority to determine the "best interests" of a disabled child. In the CRC, adults are responsible for considering the "best interests of the Child" and children are guaranteed the right to "develop healthily". What does this mean when the child is born into a body that the world declares is "unhealthy" or "disordered"? Basically, a disabled child has the right to be "fixed". Our rights comand us to manufacture an includable body for any person whose body is not "normal".

The final part of this paper's title is "Walking away from the broom closet". Ursula K. le Guin was a famous science fiction author. She wrote a book called "The Ones who Walk away from Omelas". In this book, Omelas was a Utopic society. A utopia is a place where everyone is happy and cared for. In the story, people find out that Omelas's happiness is only possible because there is a child, locked in a broom closet, who takes on all the suffering so that everyone else can be happy.

I think that in the real world, we have lots of broom closets where we make people suffer so that we can have our happy idea of normal. I think prisons are an example of broom closets. I also think that for many disabled children, the "intensive interventions" we force them to do in their "best interests" are a kind of broom closet. They suffer so that we can have our happy idea of a future without disability.

Attitudes toward children can tell us about attitudes toward the future. If we want to ensure our children do not have to be disabled, then we must also want a future where there are no disabled people. The disabled community is large and diverse. There are some conditions which are painful and some people want treatments that help them feel at peace in their own bodies. But that doesn't mean that you can eliminate disability. Disability is a natural part of human life. The society that wants to eliminate disability can only hope to eliminate itself.

I will end this summary with some stories.

On August 2, 2018, NBC News’ Health website published an article praising Google Glass

and researchers at Stanford University for the creation of a wearable app that may improve eye

contact for children with autism (Scher, 2018).

In preschool, [he] struggled socially with other kids. One hit him in the

face with a rubber mallet and another in the shoulder with a metal shovel.

“He didn’t see it coming,” [she] told NBC News. “When you don’t look

kids in the face, you can’t see their reactions or know what to expect.”

When he was 5, he was diagnosed with autism.

[N]ow 9, [he] started working one on one with a therapist using applied

behavioral analysis, a technique to improve social behavior, but [his

mother] saw little progress.

“Nothing really changed,” she said. “Until Google Glass.”

This child was assaulted by his peers. Because he was disabled, the solution was to put him in therapy. To use technology to change his behavior. To put him in a broom closet. So that other people could be happy.

In another project, researchers made a smart watch that would buzz to notify a child that they were behaving inappropriately. In this example, even "hand flapping" was considered inappropriate. At one point, "Child 5" was buzzed. He looked up and noticed that his teacher was too far away to stop him, and he continued flapping his hands. This child is my patron saint of noncompliance. His microresistance, written down in a scientific paper, is a testimony for all to see that the researchers are focusing on the wrong idea.

There are other examples, like the children who run away from robots designed to teach them social skills, or the children who scream at their therapists.

If we pay attention to where our participants are resisting our research, we can learn to recognize these broom closets, unlock the doors, and take these children out of Omelas forever.

https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/cjcr/article/view/1976

Hashtag soup

#PlainLanguage #SciComm #ScholarComm #STS #CDS #HCI #DisabilityStudies #HumanComputerInteraction #HumanRights #ChildrensRights #CRPD #CRC #Metaeugenics #Metaresistance #Eugenics #Omelas #UrsulaKLeGuin #Autism #Disability #DisabilityJustice #TechJustice #Technoableism #ColiberationLab

#plainlanguage #scicomm #ScholarComm #sts #cds #hci #disabilitystudies #HumanComputerInteraction #humanrights #childrensrights #CRPD #crc #MetaEugenics #metaresistance #eugenics #Omelas #ursulakleguin #autism #disability #DisabilityJustice #TechJustice #technoableism #ColiberationLab

Rua M. Williams · @FractalEcho

595 followers · 1052 posts · Server kolektiva.socialOn the topic of art and artists

These AI tools do not work without the data, and the data is nonconsensually scraped from artists work posted online. So the artists have had their labor stolen to train an AI system which will make the company a lot of money. They get no compensation for that.

Will the AI replace the artists? In some cases yes. For example, some companies may not want to pay an artist to make advertising materials and will use these systems to generate images instead. But overall I do not think it will significantly impact the financial condition of artists, it is just that a company is profiting off of theft. Te company is a data broker, the images they create are secondary to the data they have produced - stolen and coerced.

On the topic of face data

Is your face data a risk to you? Possibly. But the threat is more on the societal level. This data aggregation will result in tools that will be better at creating deep fakes. These are fabricated visuals that make it seem like something happened when it didn't. Just because these images are dressed up in fantasy (from the art that was scraped) the data itself can be used to produce more refined reality fakes. Also, it is possible to fake art materials, for example there could be new forms of revenge porn.

Does this make you bad for buying some pretty faces?

No. It is unusual that a company has managed to get real money from one of their data grifts. But ultimately the responsibility for the potential harms is on these companies and the state which will use these systems for future disinformation and carceral projects.

This has been an opportunity for public education in data and AI literacy.

Another thing that is an unexpected benefit to creating these images and playing with these tools is that it might help the average user get better at detecting deep fakes. There is a particular gestalt to these images that people may be better able to pick up on in the future.

I have worked in 3D art and animation for years and so I am still able to tell that something is off when I see a deep fake. It is possible that the more people who play with AI tools, the more people will be able to notice that something is off and be skeptical of the media they are watching.

*do not be a pedant about the difference between AI and machine learning I am trying to do public outreach here.

#LENSA #MachineLearning #AIArt #FaceData #DataBrokerage #DataJustice #TechJustice #DeepFake

#lensa #machinelearning #aiart #facedata #databrokerage #DataJustice #TechJustice #deepfake

Rua M. Williams · @FractalEcho

595 followers · 1052 posts · Server kolektiva.socialPart 2

A fractal is something that is shaped the same way on the outside and on the inside. When you look at it from far away, it has a shape. And when you look at it really close, it's made up of millions of pieces that have that same shape. There are some fractals in nature. Many plants like ferns, succulents, pine cones, and even some broccoli have a spiral shape that is a fractal. Lots of things made by water, like snowflakes and rivers, have a fractal shape. Trees can be fractals too. Their shape follows the same rules from trunk to root, branch to stem, and even the veins in leaves.

When I thought about NeoLiberation, I thought about Fractals. I thought about fractals because whether it was the hospital or the classroom, the group home or the community, the rules were the same. The rules that say "you cannot be here unless you act a certain way, are shaped a certain way, look a certain way".

If you lived in a state hospital, they said you were institutionalized, because you lived in an institution. Abolishing state hospitals was called "deinstitutionalization". What really happened was that many people were moved from large institutions to smaller ones. This was called "transinstitutionalization". Many of the rules were the same in these smaller homes. You still weren't in charge of your life. It was like a fractal.

Many people talked about "inclusion" as a way to make sure disabled people were together with non disabled people in the community. It was supposed to be a movement to change society so that disabled people wouldn't be kept out anymore. Instead, what often happened, was society stayed the same, and instead an "inclusion program" became one where they would work to change the disabled person so that they would "fit in". The rules stayed the same. Inclusion became like a fractal.

But remember how I said there were things in nature that were fractals? Those were beautiful things. Why are the fractals in this story so ugly?

It's because the fractal isn't the institution or neoliberalism. The fractal is us. Social relations follow fractal rules. Activist scholar Adrienne Maree Brown has also used fractals to describe social movements—“what we practice at the small scale sets the patterns for the whole system” (2017, 41).

There's something else about fractals you need to know.

The rules can be changed.

And when the rule of a fractal changes, it changes the whole shape. Inside and out. Big and small.

So neoliberalism is a rule set that makes us build ugly, violent, deadly fractals.

What rules make us build beautiful, gentle, life giving fractals?

Huey P. Newton (2019) teaches us three key things —that “everything is in a constant state of change” (193), that we must act as if our action have direct consequences on other people and the world, and that to do this you must always be thinking about how your actions change the world and that the world is always changing. To act in Solidarity with others is working together to help each other even when they are not like you, or even when they cannot help you in return. It is understanding that you have to respect someone in order to help them.

Fractals can also be people working as collective agents of change. Justice is created in collective action because it is impossible to do justice if you decide what it is for other people. Each action either keeps or changes the fractal rules. We are always at step zero in a new world and must act with the understanding that each moment is a practice of worldbuilding.

I will finish this summary by telling three stories about how disabled community can show us how to build new worlds by making new fractal rules.

Story A: Ames and Oli live on opposite sides of the country. Separated by thousands of miles, they are connected digitally and spiritually by shared experiences.

Ames: Hey

Oli: Hey!

Ames: Tag yourself, I’m executive dysfunction.

Oli: lol mood

Ames: yeah. But I really need to eat.

--incoming video call from Oli--

Ames: “Ha. Why did you call me?”

Oli: “Because we both need to eat. Let’s make lunch together.”

Ames and Oli are both neurodivergent and struggle with executive function—those cognitive processes that help you get from goal to action. Though their connection is “only” digital, this networked connection is no less real. Together, they can yoke their movements, “borrowing praxis” (Asasumasu 2015) and giving each other mutual care. By feeding themselves, they feed each other.

Story B: Every day, we check the board. We look for the names, the hospitals, the room numbers. We build the phone scripts. This one needs access to their AAC. That one needs the staff to follow the correct plan of care. That one over there needs dozens of angry phone calls to badger an admin into releasing a patient back to their community, instead of the home. The system, #BreakoutBot,6 looks up the admin phone numbers. The text messages go out. Like dandelion seeds. Thousands of angry, tired, loving crips dial in. “We are not disposable. Let my people go.

Story C: They got tired of the Zoom rooms long ago. Everyone said no, no you have to stay connected. Though they missed each other’s company dearly, they missed the absence of migraines more. It’s not that video calls aren’t “good enough” compared to other conversations…It’s just that…maybe the talking was never actually the point.

Instead, they exchange envelopes. No, not letters. They gave up words long ago. Exhausting things, words. Instead, they send crushed flowers, an interesting stone, papers etched with the skin of damp twigs…What does it mean when you send a flower and they send a stone? Well it’s not just the flower, and it’s not just the stone. The flower was purple, with white and blue too. The stone has sparkles, flint quartz, and lapis lazuli. The twigs were from the creek, where other stones were found. Maybe next week, they’ll exchange things that are round. For one it was a reminder that the earth makes beauty. For another a testament that the earth holds memory. The meanings are co-constructed, the practice collaborative. This, too, is conversation.

I will end this abruptly, because that is a very autistic thing to do. The point is this. We make the rules. We can edit all the fractals. Together.

https://catalystjournal.org/index.php/catalyst/article/view/33181/28261

#Fractals #ColiberationLab #TechJustice #DisabilityJustice #CripTechnoscience #Inclusion #Institutionalization #Neoliberalism #NeoLiberation #CollectiveAction

#breakoutbot #fractals #ColiberationLab #TechJustice #DisabilityJustice #criptechnoscience #inclusion #institutionalization #neoliberalism #neoliberation #collectiveaction

Rua M. Williams · @FractalEcho

595 followers · 1052 posts · Server kolektiva.social#PlainLanguage summary of "Six Ways of Looking at Fractal Mechanics"

This is in two parts. Yes. Even on Kolektiva where we have 10k characters.

This essay was very hard to write. Many people read it before it was finally published. Reviewers, people who read work before it is published and suggest changes, did not like my first draft. I wrote and rewrote this paper many times. I like it, in the end. But I am sorry that it is just as difficult to understand as it was to finish. I am going to try to summarize this one in plain language. I will probably have to try again when I am better at plain language writing.

One of the hardest parts about writing this paper was how often people wanted me to change the order. Another hard part was how academics do not like it when you write like an artist instead of a scholar. I am not saying that my writing is good art. But I wrote it almost like a poem, and I did this on purpose. Sometimes I think the fact that I was writing artistically is what made the reviewers so confused.

This will be both a plain language summary and a plain language story about why I wrote this paper, and how I wrote it.

These next parts are the parts that are the most like a poem. These are the parts I wrote because I wanted to help the reader to feel the things I felt. To be uncomfortable, sad, angry, but also to laugh. These were also the parts I wrote first. I first wrote these parts in the spring of 2018. The paper was not published until the fall of 2021.

Scene 1: The young women stand by their posters in the gallery. They are standing between a poster on the legacy of the sheltered workshop and the resistance of the disability community to one side and, on the other, a poster by undergraduate special education students about barriers to service access for “Adults with ASD.” Their own posters are of themselves. Their portraits, smiling. Their bullet points, describing. Their futures, absent. They stand, uncannily still, eyes deflected—on display. They have been included. They know, now that they are here, that they are here to be observed—not to be witnessed.

This scene is about something upsetting I saw at a meeting where disabled college students were presenting research. It became very clear that the students with physical and sensory disabilities had been allowed to conduct research projects, but the students with cognitive disabilities were only allowed to make posters about themselves. You could tell that they understood they had been treated differently, and that they didn't know they were going to be treated differently until they came to the meeting. There were also non disabled students presenting their research. This could have been a nice example of inclusion, except the non disabled students' research projects were about people with disabilities. Disabled students were included, but not respected.

Scene 2: He enters the auditorium. His body, familiarly unruly, comfortingly uncanny. I am entangled with cables, cursing the projector blustering about absent conference IT staff. His access needs are well known. His AAC is not a surprise. But the conference would not provide tech support, and he has been included. Equity is not justice.

This scene is about a meeting I went to where a non speaking person was presenting his work. There were ramps in the room, but no support for hooking his computer voice up to the speakers. He was included, but not supported.

Scene 3: We begin our panel. A strategic, calculated, and artful assault on the state of special education and education technology. We neuroqueer crip critics, masterful if uncanny orators, stand opposite a rookery of nonplussed vultures—special educators and their brood, here to observe autism “in the wild.” Our own people, our crip people, absent. We have been included.

This scene is about a time when I presented my work at a meeting with my friends. I was so excited to have my first chance to present my work in front of other disabled people. But most of them did not come. Some other session was more interesting to them. Instead, the people who came were mostly special education teachers. We felt like zoo animals. The only people that wanted to see us were people that wanted to compare us to their textbooks. We were included, but not loved.

Scene 4: We sit in the back of the ballroom. We pass notes like cheeky school children. We are in Autistic Space. Noises spill from his sinuses, filling the rafters on opalescent waves—sonorous, sublime. “Shhh,” they turn their vulture necks. Craning to see. Who dares to (neuro)queer this crip time? No Tourette’s, no unruly bodies. They only want us here if we can be quiet. Apparently, we are not includable.

In this scene, I was so excited to get to talk to my friend. My nonspeaking friend. To get to talk to him in his way - with pen and paper and screeches. But the only disabled people that belong at the meeting are the ones with quiet bodies. We were included, but not wanted.

These things happened at a meeting that was supposed to be run by disabled people, for disabled people. But when I was there, so many bad things happened to me and my friends. I was very disappointed, because the meeting was all about liberation, but I watched as disabled people hurt other disabled people. People were celebrating their power while disempowering others.

This is sometimes called "neoliberalism". To be neoliberal, or to do neoliberalism, is to say you are helping someone when you are only helping yourself. Specifically, it is to say you are doing something good for someone, but you are actually supporting the same system that harms that person in the first place.

Here are some examples. The Best Buddies program is a neoliberal program. It is a neoliberal program because it says it is a program to help people with intellectual disability find friends. To do this, the best buddies program signs up non disabled people who want to do charity work by being a friend to disabled people. But that's not friendship. It's pitty. So best buddies pretends to give you a friend while supporting the society that believes you can't make friends any other way.

The sheltered workshop is a neoliberal program. Sheltered workshops are neoliberal, because they say they are going to give disabled people a job, but really they are giving the disabled person a boring task for less than minimum wage. They give you a pretend job, like Best Buddies gives you a pretend friend. They support a society that believes you cannot do good work to support your community.

Many of the college programs for people with intellectual disability are neoliberal programs. They are neoliberal because they pretend you are going to college but they are really controlling what classes you can take and what you can study. They support a society that believes there are only certain things you can do with your life.

So I was very frustrated at this meeting because it was a neoliberal meeting. But it was even more frustrating because the people running it were disabled. I felt they should have known better. I joked that it was NeoLiberation. It was pretend liberation.

—

The neoliberal machine has come for inclusion.

Always watching, surveilling, assaying—neoliberalism snatches up our resistances. Categorized, analyzed, defined, discretized. Labeled. Branded. Repackaged. Capitalized.

A radical movement becomes a social movement. A social movement becomes a policy. A policy becomes a program. A program becomes an industry.

“We will be inclusive,” You say. “We will be welcoming,” You say. “We will empower you,” You say. I say, “Who is We?”

Inclusion has a flaw, you see. One that Neoliberalism has found easy to exploit. A software vulnerability, or perhaps a feature. Inclusion, unfortunately, does not necessitate the abdication of power. You offer me a seat. But it is still your table.

We are empowered to conform. We are welcomed to be observed. We are liberated into a NeoliberalLiberation.

Thanks. I hate it.

—

This feeling that I was feeling, this feeling of NeoLiberation, reminds me of a feeling that Sarah Ahmed wrote about in her book "On Being Included" - she wrote about "that feeling of coming up against the same thing wherever you come up against it." (pg. 175)

As I sat with this feeling, and thought about the "sameness", or the repetition, of what was happening between these scenes, I remembered fractals.

See reply for part 2.

https://catalystjournal.org/index.php/catalyst/article/view/33181/28261

#Fractals #ColiberationLab #TechJustice #DisabilityJustice #CripTechnoscience #Inclusion #Institutionalization #Neoliberalism #NeoLiberation #CollectiveAction

#plainlanguage #fractals #ColiberationLab #TechJustice #DisabilityJustice #criptechnoscience #inclusion #institutionalization #neoliberalism #neoliberation #collectiveaction

Rua M. Williams · @FractalEcho

314 followers · 577 posts · Server kolektiva.socialTo support public access to research, I am writing plain language summaries of the #ColiberationLab’s work in #TechJustice. Our first thread will be on a paper we wrote while I was still in school with Simone Smarr, Diandra Prioleau, and Dr. Juan Gilbert.

Summary of "Oh No Not Another Trolley"

In 2020, we sent out a survey to computer science (CS) students at universities in the United States. CS students learn about how to make computer systems.

We wanted to know how CS students think about ethics when they make computer systems. Ethics means thinking about how what you make can do things to other people. Sometimes computer systems can hurt people.

Usually, the people who get hurt the most are people who are already treated badly in society because of their race, gender, age, or disability. We wanted to know how CS students think about building systems that might hurt people.

In our survey, we shared five examples of computer systems that might hurt people, and asked CS students to tell us what they thought. The examples were of “algorithmic decision making supports”. These are computer systems that use math to help humans make choices.

Our first example was about doctors using a computer system to help them decide if a person had a disability or illness.

Our second example was about doctors’ offices using a computer system to help them decide when to schedule visits for certain patients.

In example 3, a computer system told doctors if a patient might not survive COVID, and then the doctor asked that person to sign a “Do Not Resuscitate” order. A DNR order means that if you are dying because your heart is stopping or you can’t breathe, the hospital can not help.

In our fourth example, doctors used a computer system to decide who would get a ventilator to help them breathe if there were too many people and not enough ventilators.

In our fifth example, hospitals would use a computer system to decide if someone’s personal ventilator should be given to someone else because the system thought the other person would live longer.

All of these examples were based on real things that happened during the beginning of the #COVID19 pandemic.

CS students told us what they thought the good and the bad things were about these examples.

We studied these answers to find out how CS students think about ethics problems in computer systems.

Most students believed that these systems could only do bad things if they were built wrong. Most students thought that these systems would be good “for society”.

But, when the students described society, they usually meant doctors, family members, and business owners. When the students talked about society, they talked about sick and disabled patients as if they were not members of society.

Many students did not understand what a DNR order was, and thought that it was just “useful information” and not a rule that would keep a hospital from saving your life.

Most of the students that took our survey said they thought a lot about ethics. But students also said that they did not learn a lot about ethics in their computer science classes.

Many students worried that these systems would accidentally hurt Black people more than White people. That meant that students were learning about how computer systems can be racist. But students did not worry that these systems would accidentally hurt people with disabilities.

Black people may be more likely to have an illness or disability because of how racism hurts your body. This means that even if a system is built to be “fair” about race, if it is still “unfair” about disability, the system will still be racist and ableist.

We worry that learning more about ethics will not be enough for computer scientists to build safer systems. If you don’t have strong relationships with people who are not like you, you might not be able to understand that a system is hurting people who are not like you.

That is why we hope Computer Science teachers who read this paper will think about how they can help their students become better friends to people who are not like them. When we become friends with other people, we can learn to have a “coliberative consciousness”.

A “coliberative consciousness” is when you understand how systems might hurt you AND also people who are not like you. This will help you understand how to build systems that liberate, or set free, more people.

To read more:

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9444345

Or

#ColiberationLab #TechJustice #COVID19 #ColiberativeConsciousness