Strypey · @strypey

2511 followers · 26199 posts · Server mastodon.nzoss.nz"Where Walter Benjamin claims that, since history is written by the victors, every document of civilisation is a document of barbarism, Graeber and Wengrow seek to re-write certain foundational documents. However, while Benjamin writes against the grain in the name of the oppressed, the proletariat, Graeber and Wengrow appear to do so in the name of ‘freedom’."

https://overland.org.au/2021/12/playing-with-history-a-review-of-the-dawn-of-everything/

#history #anthropology #WalterBenjamin #DavidGraeber #DavidWengrow #freedom #civilisation

#danielzola #history #anthropology #walterbenjamin #davidgraeber #davidwengrow #freedom #civilisation

☆ joene ☆ · @joenepraat

1304 followers · 27339 posts · Server todon.nlTED Talk by David Wengrow: *A New Understanding of Human History and the Roots of Inequality*

#History #DavidWengrow #DavidGraeber #archeology #anthropology #TEDtalk #books #anarchism

#Anarchism #books #tedtalk #anthropology #archeology #davidgraeber #davidwengrow #History

☆ joene ☆ · @joenepraat

1304 followers · 27338 posts · Server todon.nlTED Talk by David Wengrow: *A New Understanding of Human History and the Roots of Inequality*

#History #DavidWengrow #DavidGraeber #archeology #anthropology #TEDtalk #anarchism

#Anarchism #tedtalk #anthropology #archeology #davidgraeber #davidwengrow #History

ombra · @ombra

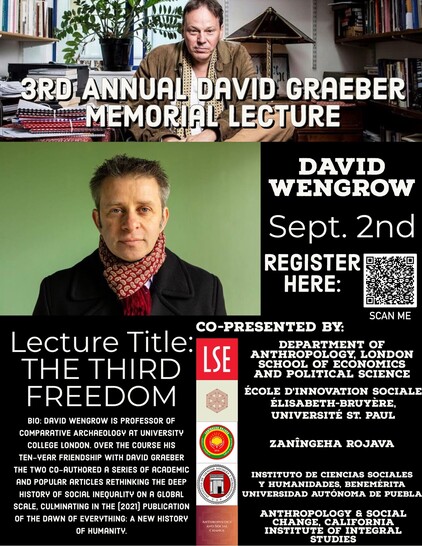

104 followers · 610 posts · Server mstdn.socialToday on the 3d anniversary of #DavidGraeber’s passing, this important lecture by #davidwengrow . It’s is coming up in just a couple of hours on 7:30 PM (Amsterdam, Berlin,...)

Register at:

https://ciis.zoom.us/meeting/register/tJArd--vpz4tGdS4ng7LgFuzG_fA9JecjZGs?fbclid=IwAR0q7nrRLlu5GVsv1nv0Rp_3OFPhguX28ZgRfFs_wCt5C9I5BGAk36crSQE#/registration

queeruferlos auf LoRa München · @queeruferlos

225 followers · 2693 posts · Server muenchen.socialDinosauriere sind religiös aber nicht zulässig: Sie kommen in der Bibel nicht vor! Die #Aufklärung verdirbt unsere Kinder! Dass es eine spannende Vorgeschichte auch demokratischer Menschen gegeben hatte, macht neben vielen anderen der #Anthropologe #DavisGraeber mit #DavidWengrow in #Anfänge klar ...

#aufklarung #anthropologe #davisgraeber #davidwengrow #anfange

Alias · @Alias

411 followers · 4067 posts · Server framapiaf.orgAujourd'hui sur Blog à part – « The Dawn of Everything », de David Graeber et David Wengrow

La disparition de David Graeber a laissé un vide, partiellement comblé par des ouvrages posthumes, comme The Dawn of Everything, écrit avec David Wengrow.

#DavidGraeber #anthropologie #DavidWengrow #Histoire #archologie

https://erdorin.org/the-dawn-of-everything-de-david-graeber-et-david-wengrow/

#archologie #histoire #davidwengrow #anthropologie #davidgraeber

ombra · @ombra

73 followers · 419 posts · Server mstdn.socialkey sentence in BBC Future article by A. Saini: “How did patriarchy actually begin?” IMO is:

"...though, there is nothing in our nature that says we can't live differently. A society made by humans can also be remade by humans. "

and as further reading I HIGHLY recommend again:

The #DawnofEverything

A New History of Humanity

Author: #DavidGraeber and #DavidWengrow

https://www.wired.com/story/david-wengrow-dawn-of-everything/

#davidwengrow #DavidGraeber #DawnOfEverything

ANTOINE. · @antoine

2 followers · 229 posts · Server mstdn.jp// #DavidWengrow : A new understanding of #humanhistory and the roots of #inequality : https://www.ted.com/talks/david_wengrow_a_new_understanding_of_human_history_and_the_roots_of_inequality?utm_source=rn-app-share&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=tedspread

#tedtalks #ted #repost #inequality #humanhistory #davidwengrow

ANTOINE. · @antoine

2 followers · 227 posts · Server mstdn.jp// #DavidWengrow : A new understanding of #humanhistory and the roots of inequality : https://www.ted.com/talks/david_wengrow_a_new_understanding_of_human_history_and_the_roots_of_inequality?utm_source=rn-app-share&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=tedspread

#tedtalks #ted #repost #humanhistory #davidwengrow

ombra · @ombra

73 followers · 419 posts · Server mstdn.social@DieterLukas

key sentence IMO is: "...though, there is nothing in our nature that says we can't live differently. A society made by humans can also be remade by humans. "

and as further reading I recommend again:

The #DawnofEverything

A New History of Humanity

Author: #DavidGraeber and #DavidWengrow

https://www.wired.com/story/david-wengrow-dawn-of-everything/

#davidwengrow #DavidGraeber #DawnOfEverything

ombra · @ombra

72 followers · 395 posts · Server mstdn.socialThe #Nebelivka Hypothesis, a collaboration between #davidwengrow & #forensicarchitecture

... at #venicearchitecturebiennale exploring the concept of #cities & #urbanism through the lens of a 6,000-year-old Ukrainian archaeological site...

Evidence suggests that its ancient inhabitants experimented with an #egalitarian form of urban life, which left a surprisingly light footprint on its surrounding environment, may ..enriched the land it occupied

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2023/may/exhibition-explores-ancient-ukrainian-egalitarian-city

#archeology #histodons

#histodons #archeology #egalitarian #urbanism #cities #venicearchitecturebiennale #forensicarchitecture #davidwengrow #nebelivka

vaPiano · @QuelFutur

7 followers · 28 posts · Server mastodon.zaclys.comLa civilisation occidentale, une imposture ? 🤨

« Une partie du problème vient de l’équivalence qui a été établie entre #civilisation et vie urbaine, puis entre ville et #État.

« Civilisation » dérive du latin civilis, un terme qui renvoie aux vertus de #sagesse #politique et d’ #entraide qui permettent aux sociétés de s’organiser sur la base de la coalition volontaire. »

#DavidGraeber et #DavidWengrow, Au commencement était...

#davidwengrow #davidgraeber #entraide #politique #sagesse #etat #civilisation

Geolexus · @Geolexus

7 followers · 50 posts · Server metalhead.clubHabe gerade angefangen, "Anfänge" (#thedawnofeverything) von #davidgraeber und #davidwengrow zu lesen und nach dem einleitenden Kapitel... Wow! Was für ein Augenöffner! (das zu sein scheint). Oder bin ich einfach zu schnell begeistert? #Harari fand ich vor einigen Jahren ja auch Wow!, aber in "Anfänge" wird die Vorgehensweise von Harari in seinem Bestseller "Eine kurze Geschichte der Menschheit" so nebenbei quasi im Vorwort beiseite gewischt. Ich bin jedenfalls gespannt, wie das ausgeht.

#Harari #davidwengrow #davidgraeber #TheDawnOfEverything

Bodhi O'Shea · @Bodhioshea

255 followers · 1081 posts · Server kolektiva.social“Very large social units are always, in a sense, imaginary. Or, to put it in a slightly different way: there is always a fundamental distinction between the way one relates to friends, family, neighborhood, people and places that we actually know directly, and the way one relates to empires, nations, and metropolises, phenomena that exist largely, or at least most of the time, in our heads. Much of social theory can be seen as an attempt to square these two dimensions of our experience.

In the standard, textbook version of human history, scale is crucial. The tiny bands of foragers in which humans were thought to have spent most of their evolutionary history could be relatively democratic and egalitarian precisely because they were small. It’s common to assume — and is often stated as self-evident fact — that our social sensibilities, even our capacity to keep track of names and faces, are largely determined by the fact that we spent 95 per cent of our evolutionary history in tiny groups of at best a few dozen individuals. We’re designed to work in small teams. As a result, large agglomerations of people are often treated as if they were by definition somewhat unnatural, and humans as psychologically ill equipped to handle life inside them. This is the reason, the argument often goes, that we require such elaborate ‘scaffolding’ to make larger communities work: such things as urban planners, social workers, tax auditors and police.

If so, it would make perfect sense that the appearance of the first cities, the first truly large concentrations of people permanently settled in one place, would also correspond to the rise of states. For a long time, the archeological evidence — from Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, Central America, and elsewhere — did appear to confirm this. If you put enough people in one place, the evidence seemed to show, they would almost inevitably develop writing or something like it, together with administrators, storage and redistribution facilities, workshops and overseers. Before long, they would also start dividing themselves into social classes. ‘Civilization’ came as a package. It meant misery and suffering for some (since some would inevitably be reduced to serfs, slaves or debt peons), but also allowed for the possibility of philosophy, art and the accumulation of scientific knowledge.

The evidence no longer suggests anything of the sort. In fact, much of what we have come to learn in the last forty or fifty years has thrown conventional wisdom into disarray. In some regions, we now know, cities governed themselves for centuries without any sign of the temples and palaces that would only emerge later; in others, temples and palaces never emerged at all. In many early cities, there is simply no evidence of either a class of administrators or any other sort of ruling stratum. In others, centralized power seems to appear and then disappear. It would seem that the mere fact of urban life does not, necessarily, imply any particular form of political organization, and never did.

This has all sorts of important implications: for one thing, it suggests a much less pessimistic assessment of human possibilities, since the mere fact that much of the world’s population now live in cities may not determine how we live, to anything like the extent you might assume . . .”

Bodhi O'Shea · @Bodhioshea

256 followers · 1073 posts · Server kolektiva.social"Ever since Adam Smith, those trying to prove that contemporary forms of competitive market exchange are rooted in human nature have pointed to the existence of what they call ‘primitive trade.’ Already tens of thousands of years ago, one can find evidence of objects — very often precious stones, shells or other items of adornment — being moved around over enormous distances. Often these were just the sort of objects that anthropologists would later find being used as ‘primitive currencies’ all over the world. Surely this must prove capitalism in some form or another has always existed?

The logic is perfectly circular. If precious objects were moving long distances, this is evidence of ‘trade’ and, if trade occurred, it must have taken some sort of commercial form; therefore, the fact that, say, 3,000 years ago Baltic amber found its way to the Mediterranean, or shells from Mexico were transported to Ohio, is proof that we are in the presence of some embryonic form of market economy. Markets are universal. Therefore, there must have been a market. Therefore, markets are universal. And so on.

All such authors are really saying is that they themselves cannot personally imagine any other way that precious objects might move about. But lack of imagination is not itself an argument. It’s almost as if these writers are afraid to suggest anything that seems original, or, if they do, feel obliged to use vaguely scientific-sounding language ( ‘trans-regional interaction spheres’, ‘multi-scalar networks of exchange’) to avoid having to speculate about what precisely those things might be. In fact, anthropology provides endless illustrations of how valuable objects might travel long distances in the absence of anything that remotely resembles a market economy.

The founding text of twentieth-century ethnography, Bronislaw Malinowski’s 1922 Argonauts of the Western Pacific, describes how in the ‘kula chain’ of the Massim Island off Papua New Guinea, men would undertake daring expeditions across dangerous seas in outrigger canoes, just in order to exchange precious heirloom arm-shells and necklaces for each other (each of the most important ones has its own name, and history of former owners) — only to hold it briefly, then pass it on again to a different expedition from another island. Heirloom treasures circle the island chain eternally, crossing hundreds of miles of ocean, arm-shells and necklaces in opposite directions. To an outsider it seems senseless. To the men of the Massim it was the ultimate adventure, and nothing could be more important than to spread one’s name, in this fashion, to places one had never seen.

Is this ‘trade’? Perhaps, but it would bend to breaking point our ordinary understanding of what that word means. There is, in fact, a substantial ethnographic literature on how such long-distance exchange operates in societies without markets. Barter does occur: different groups may take on specialties — one is famous for its feather-work, another provides salt, in a third all women are potters — to acquire things they cannot produce themselves; sometimes one group will specialize in the very business of moving people and things around. But we often find such regional networks developing largely for the sake of creating friendly mutual relations, or having an excuse to visit one another from time to time; and there are plenty of other possibilities that in no way resemble ‘trade.’

Let’s list just a few, all drawn from North American material, to give the reader a taste of what might really be going on when people speak of ‘long-distance interaction spheres’ in the human past:

Dreams or vision quests: among Iroquoian-speaking peoples in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries it was considered extremely important literally to realize one’s dreams. Many European observers marveled at how Indians would be willing to travel for days to bring back some object, trophy, crystal or even an animal like a dog they had dreamed of acquiring. Anyone who dreamed about a neighbor or relative’s possession (a kettle, ornament, mask and so on) could normally demand it; as a result, such objects would often gradually travel some way from town to town. On the Great Plains, decisions to travel long distances in search of rare or exotic items could form part of vision quests.

Traveling healers and entertainers: in 1528, when a shipwrecked Spaniard named Alvar Nuriez Cabeza de Vaca made his way from Florida across what is now Texas to Mexico, he found he could pass easily between villages (even villages at war with one another) by offering his services as a magician and curer. Curers in much of North America were also entertainers, and would often develop significant entourages; those who felt their lives had been saved by the performance would, typically, offer up all their material processions to be divided among the troupe. By such means, precious objects could easily travel long distances.

Women’s gambling: women in many indigenous North American societies were inveterate gamblers; the women of adjacent villages would often meet to play dice or a game played with a bowl and plum stone, and would typically bet their shells beads or other objects of personal adornment as the stakes. One archeologist versed in the ethnographic literature, Warren DeBoer, estimates that many of the shells and other exotic discovered in sites halfway across the continent had got there by being endlessly wagered, and lost, in inter-village games of this sort, over very long periods of time.

We could multiply examples, but assume that by now the reader gets the broader point we are making. When we simply guess as to what humans in other times and places might be up to, we almost invariably make guesses that are far less interesting, far less quirky — in a word, far less human than what was likely going on.”

Bodhi O'Shea · @Bodhioshea

256 followers · 1071 posts · Server kolektiva.social“The freedom to abandon one’s community, knowing one will be welcomed in faraway lands; the freedom to shift back and forth between social structures, depending on the time of year; the freedom to disobey authorities without consequence - all appear to have been simply assumed among our distant ancestors, even if most people find them barely conceivable today. Humans may not have begun their history in a state of primordial innocence, but they do appear to have begun it with a self-conscious aversion to being told what to do. If this is so, we can at least refine our initial question: the real puzzle is not when chiefs, or even kings and queens, first appeared, but rather when it was no longer possible simply to laugh them out of court.”

Bodhi O'Shea · @Bodhioshea

256 followers · 1070 posts · Server kolektiva.social“American citizens have the right to travel wherever they like - provided, of course, they have the money for transportation and accommodation. They are free from ever having to obey arbitrary orders of superiors - unless, of course, they have to get a job. In this sense, it is almost possible to say the Wendat had play chiefs and real freedoms, while most of us today have to make do with real chiefs and play freedoms. Or to put the matter more technically: what the Hadza, Wendat or ‘egalitarian’ people such as the Nuer seem to have been concerned with were not so much formal freedoms as substantive ones. They were less interested in the right to travel than the possibility of actually doing so (hence, the matter was typically framed as an obligation to provide hospitality to strangers). Mutual aid - what contemporary Europeans referred to as ‘communism’ - was seen as the necessary condition for individual autonomy.”

Bodhi O'Shea · @Bodhioshea

256 followers · 1069 posts · Server kolektiva.social“In other words, there is no single pattern. The only consistent phenomenon is the very fact of alteration, and the consequent awareness of different social possibilities. What all this confirms is that searching for ‘the origins of social inequality’ really is asking the wrong question.

If human beings, through most of our history, have moved back and forth fluidly between different social arrangements, assembling and dismantling hierarchies on a regular basis, maybe the real question should be ‘how did we get stuck?’ How did we end up in one single mode? How did we lose that political self-consciousness, once so typical of our species? How did we come to treat eminence and subservience not as temporary expedients, or even the pomp and circumstance of some kind of grand seasonal theatre, but as inescapable elements of the human condition? If we started out just playing games, at what point did we forget that we were playing?”

poratlu · @poratlu

39 followers · 650 posts · Server scicomm.xyz@bstacey @DarlavdRiet @JamesGleick @ftrain Even if #DunbarsNumber exists, it’s not clear it means much? As #DavidGraeber and #DavidWengrow wrote, it’s not just modern cities or sports teams that have stretched far beyond any supposed limit. Native Americans or Australians would long ago travel half a continent to hang out with fellow clan members they weren’t related to and hadn’t met. Dunbar hasn’t limited humans for millennia, if he ever did.

#davidwengrow #davidgraeber #dunbarsnumber

José Manuel Barros · @Barros_heritage

177 followers · 251 posts · Server home.socialOn the Propylaeum ebooks website it is possible to download several amazing books. In particular, I want to highlight Image, Thought, and the Making edited by David Wengrow and published in 2022 (licensed under a Creative Commons License 4.0).

https://doi.org/10.11588/propylaeum.842

#Visual #Image #SocialWorlds #DavidWengrow #Archaeology #Anthropology @academicchatter @histodons @anthropology

#visual #image #socialworlds #davidwengrow #archaeology #anthropology