Chris Sanders 🔎 🧠 · @chrissanders88

1477 followers · 252 posts · Server infosec.exchangeThe alert tells you that one artifact of Bazar has been discovered. Your first task should be finding at least one other Bazar artifact to determine if the malware has actually infected the system.

With any alert that mentions named malware, you’ve got a leg up because you can leverage everything the world already knows about the malware. But, you’ve got to do the research work! Some Googling reveals lots of published information about Bazar. For example, check out these two articles:

1. https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/bazarloader-network-reconnaissance/

2. https://www.fortinet.com/blog/threat-research/new-bazar-trojan-variant-is-being-spread-in-recent-phishing-campaign-part-I

From these articles, you want to look for artifacts that are easy to find given the evidence sources you have available. Ideally, those artifacts are tied to events in the timeline near the event you already know about — the potential C2 traffic. For example, you could…

1. Look for C2 network traffic that matches the pattern in the article

2. Identify executions of new DLLs

3. Seek newly written registry RUN key entries

Among other things…

Not many folks in the replies actually did research on the malware, but a few did mention doing it. My response of the week goes to @thomaspatzke, who captured some of those ideas (https://infosec.exchange/@thomaspatzke/109788268480096606). Doing research is part of the job and a skill to develop. It involves identifying relevant info, synthesizing it, and knowing your evidence sources well enough to focus your efforts. You get better at it by doing it more and internalizing feedback on what works and doesn’t. Lots of analysts feel like spending time reading about malware is distracting them from the real world of looking at the evidence. Overcome that worry -- doing that reading when alerts like this come up is a core part of the work.

By the way... if you were at the #CTISummit, I did some live forecasting for this scenario 😄

Speaking of research… some folks focused on network artifacts while others focused on host artifacts. Where do you normally focus? In what circumstances might that limit you? That’s something to think about… 🚀 #InvPath #DFIR #SOCAnalyst #ThreatIntel

#ctisummit #invpath #dfir #socanalyst #threatintel

Chris Sanders 🔎 🧠 · @chrissanders88

1408 followers · 212 posts · Server infosec.exchangeThis week’s investigation scenario was all about research — a critical function of the analyst.

Original Scenario: https://infosec.exchange/@chrissanders88/109665506345228679

Most folks Googled the UA string, and that’s a good idea! But, this one was a little bit deceptive because it required more work than you might think.

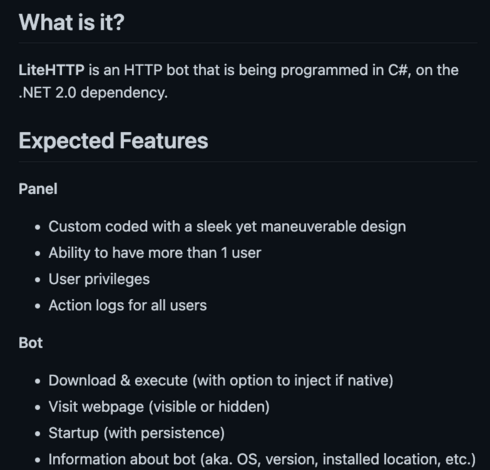

If you Google the string, the first result that comes up is a github repo for a C# HTTP bot someone wrote named LiteHTTP. The code makes it look like the bot uses the string I shared as its user agent: https://github.com/zettabithf/LiteHTTP/blob/master/Bot/LiteHTTP/Classes/Communication.cs. If you think about the scenario I described, I said that this was a LINUX host, but this bot is written for a WINDOWS system. At that point some folks said case closed, because the Windows bot won’t run on Linux. But… there’s more to the story.

If you start to look at the other search results, you’ll find quite a few others things. That includes..

1. A ProofPoint article about a cred theft tool called Ovidly

2. A Sandbox report about a suspicious Perl script

3. A Checkpoint article about a Linux trojan named Speakup.

BTW, Shout out to Harlan on LinkedIn, who was my response of the week for going beyond the first result and identifying these other things: https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7018592428894949377?commentUrn=urn%3Ali%3Acomment%3A%28activity%3A7018592428894949377%2C7018634119542702081%29

This scenario demonstrates some of the difficulty analysts may go through when researching known threats. Even though this string appears pretty unique, it’s easy to assume that the first result you find is all-encompassing. In truth, each source you examine may only have a piece of a broader puzzle.

For this example, you may have found that the string from the scenario is actually the MD5 hash of the word liteHTTP. But, looking through multiple sources, you’ll also find some analysis that makes it clear that some code from the liteHTTP bot appears to have been reused across some of this other malware. That makes sense! Some of these articles suggest that the same author might be responsible for multiple strains of malware, but it could also be that someone simply borrowed from the code that’s publicly available on github. That’s pretty common.

So, how do you approach this? We’re dealing with a Linux system and we’ve found one article that mentions a linux infection https://research.checkpoint.com/2019/speakup-a-new-undetected-backdoor-linux-trojan/, so that’s the place to start trying to match up some of the described capabilities with what we can find on our system. I might start by looking for some of the victim registration commands that the tool reportedly executed post-infection… things like uname, ifconfig, arp, and so on. After that, I might also try to validate that the network traffic matches the format seen in samples mentioned in the article. I’ve probably confirmed an infection at this point, and because the tool has the ability to infect other systems on the network, I’m going to start looking at internal communication and authentication from this system to others that began around this time. That’s not the whole path, but it’s a start.

Also, keep in mind that completely new and unique malware could arise based on the openly available code we’ve discovered. That means we might be dealing with an entirely new set of capabilities that aren’t yet documented anywhere yet. Similarly, this malware could be used to deliver other malware. In one report we see it led to an eventual infection by a cryptocoin miner, but that could easily change to something else. In that case, the analysis may be a bit broader… looking for any suspicious executions or newly established persistence mechanisms in common locations, among other things during this time period.

A lot of the work an analysts does will be researching threats to figure out what you need to look for on your network to see if that threat has manifested there. It may feel like that’s secondary to the primary job role, but it’s a central task in the analysts work and a skill to develop.

BTW, there are some public threat intel sources that are well suited for specific searches with common artifact types you’ll run across. Do you have some reliable favorites? That’s something to think about… 🚀 #InvPath #DFIR #SOCAnalyst #ThreatHunting #infosecurity

#invpath #dfir #socanalyst #threathunting #infosecurity

Chris Sanders 🔎 🧠 · @chrissanders88

1409 followers · 212 posts · Server infosec.exchangeSo many great responses to this scenario. The thing I want to focus my discussion on is clarifying the role of the file. A lot of you did the right thing here by Googling the file type. It’s traditionally associated with Doom (the game). However, that doesn’t mean the sample we found was associated with Doom. It could be a coincidence (random/another tool that also uses that extension) or an intentional collision (for fun/to deceive).

If it’s not related to Doom, does that mean you wasted time researching the file extension? Absolutely not! That research is still a good idea here. It’s low effort, often high reward, and it’s knowledge you can carry forward next time you encounter something similar.

If you do want to take the approach that you should disprove the file is associated with Doom, you can open it up in a hex editor and compare its structure to a Doom WAD file to see if it matches ([https://bw.vern.cc/doom/wiki/WAD](https://bw.vern.cc/doom/wiki/WAD)). Shout out to @da_667 who mentioned that and even did some research to find a reference for the file structure. He had more good ideas in his post, and is my response of the week this time around.

Another strategy is to approach the file more generally without the assumption it’s Doom related. There are many routes to go, but you want to start with things that are high value and low effort. Either way, you can't just trust that it's Doom. If you can determine the true file format, that will shape the rest of your analysis. You can look at the first few “magic” bytes to try and determine a file type ([https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_file_signatures](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_file_signatures)) or maybe use the Linux file command.

If you can figure out what type of file you’re dealing with, you can often open and analyze the file in tools that are purpose built for it. For example, if you figure out it’s a sqlite DB file, you could open it in SQLite Database Viewer to see what data is contained there.

Analyzing the strings (FLOSS/CyberChef) or opening it in a text/hex editor are great ideas. It could be a config file or script…something easy to parse visually. You can also look for things like domains and IP addresses, obfuscations, or nefarious functional calls.

After that, you get into searching public sandboxes for the file hash, dropping the file into your own sandbox for behavioral analysis (if it’s executable), looking at other metadata, or performing some static analysis. All in effort to understand the file’s role.

Once again, with so many paths to take the key is focusing on the paths with the best balance of low effort to high reward. Understand what you’re dealing with so you can use the right tools, then move forward. There are lots of good ideas in the responses around other things to be done at this point — prevalence on the network, associating the file with a specific user, and more. But, this investigation really hinges on understanding the role of the file.

By the way, a couple folks mentioned that the file could be encrypted! How would you determine if a file was encrypted, simply obfuscated, or in clear text? That’s something to think about… 🚀 #InvPath #DFIR #SOCAnalyst

Chris Sanders 🔎 🧠 · @chrissanders88

1357 followers · 174 posts · Server infosec.exchangeTheories about this one had RANGE! The benign/technical (malfunctioning mouse), the benign/no-tech (use mis-reported), the benign/low-tech (a prank with a wireless mouse), and the malicious/high-tech (attacker used remote mgmt software)… among others!

A lot of folks posited their “most likely” explanation. When we forecast possible timelines, the one we want to pursue is usually the one that is some combination of the most likely + the quickest to investigate. Whatever path you pursue, you want to be deliberate about it. Try to prove or disprove your hypothesis quickly, remembering that disproving is often faster when possible. You only have to disprove it once, but you might have to collect a lot of evidence to prove it.

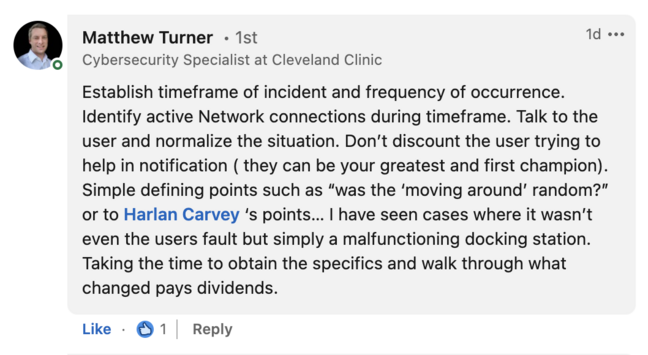

Right off the bat, getting as precise a time range for the activity as you can is helpful, because a lot of the queries you’ll make (executions, file reads, device use, etc) will begin within that range so you can find out what exactly happened on the system. Should out to Matthew Turner, who mentioned the importance of establishing the timeframe and clarifying what the user saw. That's my response of the week. Some of this hinges on just how random or intentional the mouse movements were. https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7010983533867409408/?commentUrn=urn%3Ali%3Acomment%3A(activity%3A7010983533867409408%2C7011376618833158144)&dashCommentUrn=urn%3Ali%3Afsd_comment%3A(7011376618833158144%2Curn%3Ali%3Aactivity%3A7010983533867409408)

In terms of the pranks, looking for new devices plugged into the system around this time frame works (on Windows, you’re looking in the registry or event logs). You could also inventory wireless devices in the near area and try to see if those were plugged into the system. Of course, beware that some of the reported info about USB devices isn't always as it seems: https://www.sans.org/blog/the-truth-about-usb-device-serial-numbers/.

For potential malicious use of remote management software, you’re likely looking for newly installed or running and executed processes tied to those tools. You’ll consider the commercial and free tools (TeamViewer, VNC, etc) along with the explicitly malicious RATs. Not for nothing, you should also consider whatever software your support team uses for remote troubleshooting. It could be a support person using that tool to fix something or mistakingly connecting to the wrong system. Either way, check your ticketing system and the app logs 😂

I actually investigated this scenario once. The box was clean, but we did find evidence that some other wireless USB mice had been plugged into it at various times. Ultimately, nobody fessed up, so it remained an unsolved mystery.

One more interesting facet of this case to consider… the user SAW the mouse moving. Some remote access tools lock the screen under remote control, and others don’t. Do you know which is which? Something to think about… 🚀

#invpath #dfir #socanalyst #digitalforensics #threathunting